WALK THROUGH FIRE

FEBRUARY 23, 2020

In the pond above our house, the water could be smooth as glass, except for a few water skippers that glided across the surface. My brothers, sisters, and I would gather flat stones and throw them into the still water, and watch the waves roll to the shore. One wave would come in, then another. The effect continued until somewhere along the way it softened, and eventually there was nothing more than a gentle lapping. Certain experiences in life soothe us like the soft caress of a spent wave, but others are forced upon us, hitting us like a stone breaking a still surface of water. At the age of five, my idyllic country life would be shattered, the gentle calm overcome by a sudden force followed by a series of crashing waves.

The day started as nondescript and ordinary as any other. Driving back from my grandmother’s house in Carlsbad, I heard my dad grumble to my mom that he had to check on the Weed Tower cattle guard. My brother and two sisters sparred in the back seat. My mother stared out the window. I could see her downturned mouth. But my dad’s short, clipped statement meant he was going to get the job done. For my siblings in the back seat, that signaled that they’d better quiet down, stop fighting, or someone would be crying any minute. What my dad couldn’t have known at the time was our family would be irrevocably changed with that one decision. We would feel the sting of lost innocence. We would live through it, but the warm, insulating life we once had would be gone.

My childhood home

Stone Fireplace–Our only heat

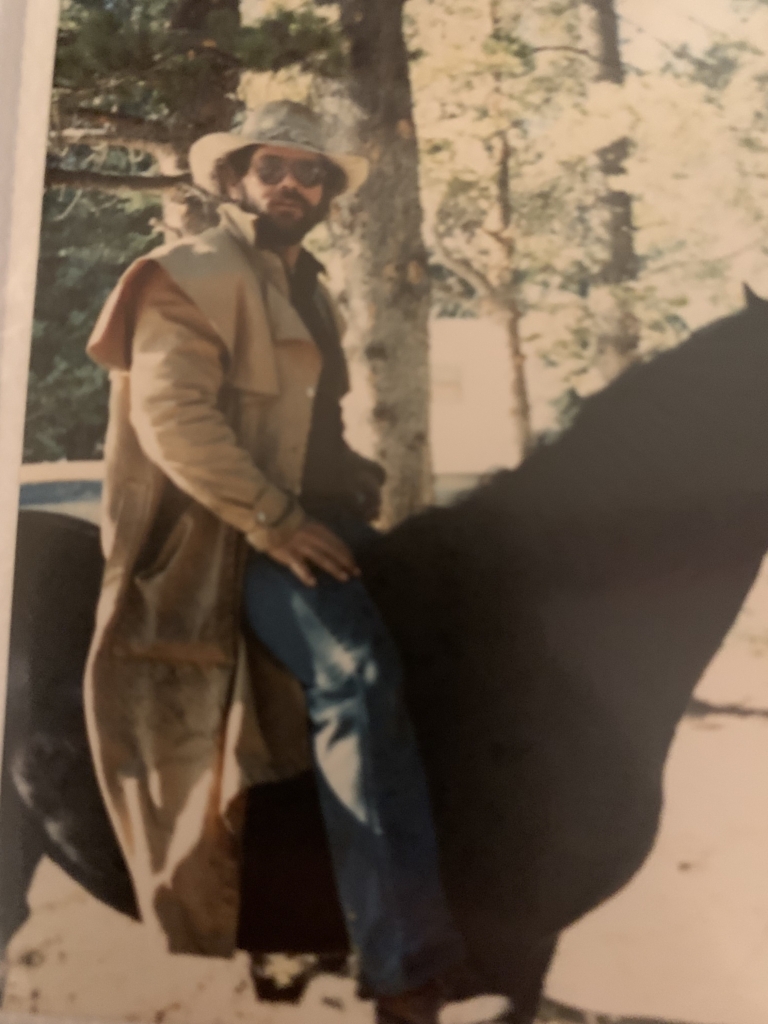

My dad had been good looking. He was proud of his curly, dark hair and strong physique. He had worked hard in the potash mines for years, and now he had a chance to put that kind of labor behind him. He took a job with the forest service and ranched his own land. He had built a good life in the bucolic mountains of New Mexico. He wanted us to be happy because his own upbringing had been less than perfect. He waxed in and out of depression, often becoming anxious and restless. One minute, euphoria, the next a deep melancholy that not even his children could pull him from. He’d talk of great men and their ability to make their mark on the world. He wanted to be someone, a man of prestige, clout, and affluence. He didn’t realize that the people sitting in that Dodge sedan was everything he needed to be happy. But his memories of living in poverty after his mother left his father zapped his confidence. Then, at fourteen, he learned the mean trick of irony. Right outside a desolate town called Hope, his father, Henry, had driven his diesel truck too fast around a bend and lost control. Henry died in that wreck, and my father could never quite put it behind him. My dad’s physical strength didn’t translate into internal strength. His mood frequently clouded over, and gloom would set in.

We had been in the car for two-hours driving from my Grandma Julia’s house in Carlsbad to our home in Sacramento. In those days, cars had bench seats in the front and back. I could spread my little five-year-old body out with my head on my mother’s lap and dangle my feet over the seat edge. But on this day, I kept pushing my heels into my dad’s side, and he kept brushing them away. His brow tensed, and he snapped, “keep your feet down.” In the back seat, my sisters and brother were still punching one another and laughing. My dad turned off the main highway onto the forest service road to Weed Tower. Rocks spit from the spinning tires, and the engine growled as we climbed the mountain. He took the curves tightly, twisting around ever so often to backhand one of my siblings. They bobbed and weaved, knowing the trouble they were in, but unable to contain their restlessness. My mother never said a word. Discipline was dad’s domain.

After winding up the hill a little too fast and trying to subdue the troops in the back, he skidded to a halt. The car lurched forward as he put it in park. Without a word, he jumped out and walked over to the tented cattle guard. My mom waited in cold silence with us.

In the west, cattle guards are used to either keep cows in or out of a particular area. A deep pit is dug in the middle of the road then lined with cement. Parallel metal bars are laid long ways across the pit. Each bar is spaced four inches apart. The bars are sunk into cement at opposite ends. Above the ground, posts at opposite ends are strung with barbed wire fencing. This device replaces a gate; cars can pass over the cattle guard, but cows recognize the potential hazard of breaking a leg and won’t step across.

It was one of my dad’s jobs to make sure the cement didn’t crack in the cool, New Mexican evenings. We were at an altitude of 8,000 feet. When cement cures, it shouldn’t fall below 50 degrees Fahrenheit. A fifteen-foot long tent was placed over the top of the cement with a furnace inside. My dad had to check the furnace in order to keep the temperature just right.

Growing up in a little mountain village—with cows, horses, pigs, our dog Rebel, beloved cats Tiger One, Tiger Two, and Toughie—was as good as it gets. We lived across the field from my dad’s mom, Grandma Mame. She never followed the rules, which we loved. As we hopped rocks to cross the gurgling creek to get to her house, she would stand with her hands on her hips and laugh. On many occasions we sneaked over to watch Elvis movies, mostly because my mom was in an extreme religious phase and didn’t approve of his gyrations or suggestive songs. My oldest brother, Ronnie, and I loved Elvis, and so did Mame.

Our house was a log cabin. It had original hand-hewn beams with interlocking ends and plaster that filled the crevices. It was rustic, but beautiful. I remember people coming up our drive just to take pictures of the old place. About a quarter of a mile above the house was the pond, fed by an underground spring. In the summer we would put on our swimsuits and jump into the frigid water. In the winter it became a frozen sheet of ice.

I loved my home. I embraced the beauty of it. I was just a child, but it was perfect. Even when my parents fought and my mom threw plates at my dad, I knew my brothers and sisters would take me to a massive tree swing where a thick-corded rope had been hung. We would swing and talk. My oldest brother, Ronnie, would reassure us that no matter what happened, he would take care of us. Eventually, after my mother’s temper calmed, and the threat of flying plates were over and the white flag was raised, my dad would come up the hill and tell us, “mom has cooled off.” He knew he had once again pushed her too far. We had some crazy moments, but we were loved, and we were safe.

But then the stone crashed through the calm surface of the pond and the waves rushed out, hard and fast with repercussions for years to come. My dad disappeared into the tent just as one of our neighbors pulled alongside the Dodge. His name was Charlie, and we had known him for as long as I could remember. Sometimes we would go to his house where my parents would play cards with him and his wife, Pansy. I would play with their only son, Lonnie Joe. Charlie got out of his pickup truck and my mom got out of our car.

Charlie and my mom chatted. I played with the blinker on the steering column, pretending to drive, when something caught my eye. I turned to look at the tent. The sides sucked in as if it were a living, breathing beast. Then, without warning, the tent exploded, exhaling fire high into the air. I watched a scene my mind could not quite comprehend. What I did realize all too soon was that my dad was still inside.

We all saw it. But it was my mom who ran toward the tent, shouting my dad’s name. Charlie pulled her back. Just as suddenly, he took out his pocketknife and began cutting gashes into the canvas so there would be a means of escape if my dad could find the holes. The fire burned Charlie as he kept slicing into the tent. The trench underneath was engulfed in flames. Inside the car, we were four stoic soldiers. No one moved. It was as if we all knew this would be a severe and dramatic change, and it would be painful.

The flames darted higher, and my mother screamed my dad’s name. In the car, we held our collective breath. Suddenly a charred and blackened form staggered from the inferno. He couldn’t have been in there that long, but his appearance said otherwise.

Charlie grabbed an old horse blanket from his truck and extinguished the last of the flames from my dad’s body. He and my mom gingerly sat my dad in the backseat of the Dodge. My mom got into the driver’s seat. Charlie said he would go to the nearest phone and call for an ambulance. Alamogordo was the closest town. Mom said she would look for the ambulance on the way, and we were gone. She pressed the accelerator and we sped down Denny Hill, descending 3,000 feet in a matter of minutes.

Dad sat in the back with my brother, Duane, and my sister, Larena. My oldest sister, Ragina, got up front with mom and me. Dad kept talking, his words fast, repetitive. He’d gasp, then he’d whistle. His body shivered and shook. He was cold, but couldn’t stand anything near his burned skin. The flesh on his fingers hung in loose ribbons. I looked back at him. Like a slow movie frame, that moment pressed into my mind with the smell of burning flesh, skin hanging off of his hands, his once handsome face, red and swollen, and now unrecognizable.

He kept saying, “It’s going to be okay, kids. Don’t worry about your old dad.” Instinctively, I knew nothing would be okay.

We made it to Alamogordo, never passing the ambulance that Charlie called. Later we heard that they had taken a different road, which can happen in the country.

My memory is vague after that. I was five. But I do remember my Grandma Mame being with us. We were sitting on the lawn of the hospital, and it was dark. Mame said, “look up at that window. That is where your dad is, and you need to say a prayer for him.” It’s hard for a five year old to know what to say to God when your dad has just walked through fire. In a moment like that I should have cried. As far as I know, none of us cried then, or ever.

After almost a year of hospitals and skin grafts, my dad finally came home. He had third degree burns over 90% of his body. He had no hair, no eyebrows, and barely any eyelids. Skin had been grafted to rebuild his nose. I wanted to run up and hug him, but my mother stopped me. “You can’t; it’s too painful.”

It would be years and many surgeries later before he healed physically. The new skin on his hands continually cracked and bled. Eventually his hair grew back, but his nose looked like stretched putty. Raised patchy welts (which would later become raised patchy scars) covered his arms and legs. His skin was a mottled red and pasty white.

He stayed home for some time after the accident. When my mom went to work, my dad felt like half a man. Then came the assumptions that she couldn’t face his appearance, then accusations that she wanted someone else. When a person’s identity is torn away, they say and do hurtful things. He had lost who he was. That handsome and physically strong man was now weak and broken. His insecurities mounted day by day. When my mom worked late, we stayed with dad, and I dreaded his sulking, surly tirades. After the fire, he could be quite mean.

We stayed in Sacramento two years after the accident, and then my mother could no longer deal with the depression—his or hers. After much debate, and Mame’s disapproval, we left our mountain paradise to move to Carlsbad, where my mom and dad found jobs. By that time the marriage had been damaged even more than my father’s features. My dad got his job back in the underground potash mines, and he hated it. My mother took classes to become a nurse in the ER. We came to a town where people looked at my brothers, sisters, and me like hicks from the hills (and we were). When my parents divorced, the split wasn’t just between them; it split us all. Soon we dispersed like ants out of an anthill. My oldest brother left for Texas, and Duane took off on his chopper for California. My sisters married too young, exchanging opportunity for an endless cycle of child rearing and bad decisions. My path was circuitous, with its share of self-inflicted suffering. The slap of the waves continued to hit again and again, and we fought to stay afloat. But still the tragedy that was forced on us would somehow be softened by the memory of that calm, placid pool of our peaceful mountain life.