DUANE

1991

Three fragmented images keep coming to mind when I think of my brother, Duane. Short clips like a slideshow giving a glimpse into his last days. These snippets are what became of the week leading up to that one last sad event. My brother had a premonition. A feeling so profound, he told his wife he could not shake it. So he went out and bought her a good car with a solid transmission. He somehow knew she would need it to make several long journeys without him. The next thing he did was insist that his dog, the one that always jumped into the truck to accompany him on the road to Greenriver, stay home. And last, minutes before he began the 200 mile drive to work in a factory that makes baby’s diapers, he tried to call our mother. She wasn’t home, so he left a message, hopped into his truck, sans the dog, and took off on the last trip of his life.

Tragedies happen to people all the time. But when it hits close to home it feels like time stands still. The world whirls around you, but you are only aware of that single painful emotion welling up from deep inside. It squeezes your heart as you choke back the tears, and the clock stops, as memories flood to the surface.

My brother was a simple guy. He loved to hunt, fish, and spend hours in his workshop creating beautiful things. He was an inventor. He made a weird-looking gadget to extract metal fence posts from the ground. In the west, ranchers use metal posts to mark off their property, then they fence the area with barbed wire which is strung tightly between each one. Every now and then you have to move a fence, and that can be impossible without the right device. Duane had severe OCD and ADHD but he managed to invent this device using an old American car jack that extracted the posts with ease. He then got it patented.

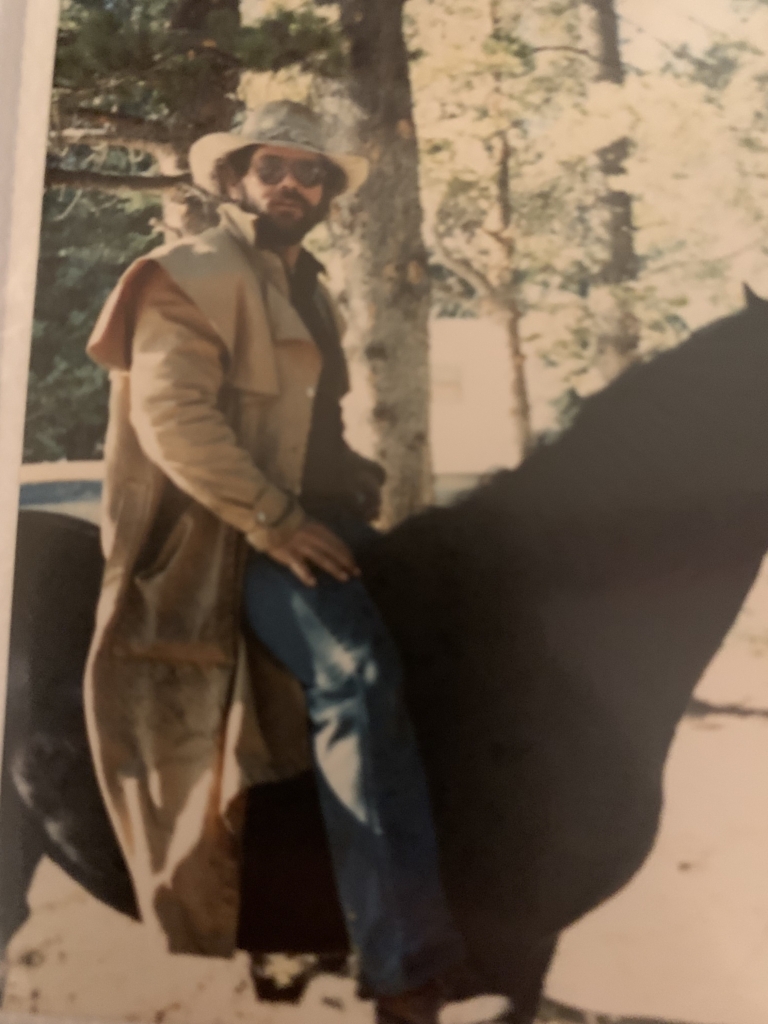

At one point in Duane’s life he had been a biker. He had a bushy beard, long hair, and a bike with extended forks like the ones in the movie, Easy Rider. I would like to say he was one of those free spirits that took to the road to find himself, but for my brother who never quite fit in, I believe he was really trying to run away from judgment and ridicule. We had moved from a beautifully pristine country life in the central mountains of New Mexico down to an ugly little corrosive eastern desert town. People were harsh and petty and let us know that we did not fit in. I was eight when we moved there, and Duane was fourteen. My brothers and sisters hated it, and none of us ever wanted to stay. So, as soon as we could, most of us got out.

Later on when our parents divorced, the entire family fell apart. We all scattered, trying to understand the bad news. At that time I was seventeen, just graduated high school and decided to move to California. One summer day, Duane showed up at my door. He also was living in California, but farther north. We had not seen each other in several months, but we were still reeling from our family’s collapse. I guess moving to California was a way to distance ourselves from the chaos. We went to lunch in one of those non-descript cafeterias. As we went through the line picking out mashed potatoes and over-cooked green beans, the silence between us was deafening. We tried to fill the uncomfortable gaps with a few shared family moments, but we were empty, unmoored, and lost. We moved mechanically through our lunch both trudging through impossible emotions.

On the way down from Bakersfield, his bike tire had popped and he’d hitch-hiked all the way to my place in Long Beach from the outskirts of LA. We walked to a motorcycle store and he got the tire patched. He needed a ride back to where he’d stashed his bike. I had a friend with a car and she agreed to give him a ride. How my brother knew where the chopper was hidden along the 405, I’ll never know. But in the dark, on a non-descript freeway he knew the exact spot where he had dragged the bike up a hillside, and covered it with brush. For a guy who struggled to read and transposed his numbers, his instincts were spot on. He put the tire back on, and was gone.

He was like that. He could study anything mechanical, anything electronic, take it apart, then reassemble it without a hitch. When he rode off, hair flying behind him (no helmet), the growl of the chopper fading into the night, I ached for both of our empty lives. We were grieving strangers from a shared childhood. We were damaged and lost. Neither knew exactly why our family had disintegrated, but somehow for years we knew it was coming. We had not yet examined those circumstances closely, maybe because we had hoped for a better outcome. One that would give us strength and comfort, and a foundation that was solid. As it turned out, the inevitable happened, and I couldn’t comfort him, and I didn’t understand him. But, as he drove away that day, I hated myself for being cold. I hated myself for being empty. I hated myself for not giving words of comfort and support.

After I moved back to New Mexico to go to college I had a little apartment in Albuquerque. I had not seen my brother for several years, but once again he appeared on my doorstep. This visit was much like the one in California, only this time he was in a cast from his waist to his neck. He’d been in a bad motorcycle accident. He and his girlfriend, Drifty, had gotten behind an old truck with a load of crap in the back. The truck had slowed. When my brother sped up to go around, the truck turned in front of him. No blinker, no warning, just a quick turn to the left. Duane tried to avoid the truck. The bike slid to the ground and my brother slid with it, but Drifty didn’t make it. She landed under the truck and died instantly. I didn’t know how to talk to my brother about the death of his girlfriend. I felt that old familiar void, but this time I was angry.

Why was my brother lost in this kind of limbo? Where were my parents in all this, and why wasn’t he in college, or some kind of training? Why was he still wandering around flirting with death? I listened as he told me what had happened. I listened as he made a phone call to his girlfriend’s family, sobbing, and saying how sorry he was. He needed forgiveness so that the open wound of grief would heal. I couldn’t say anything. I was as stuck as he was, and maybe that is why I had nothing to give. My only emotion was anger and that was directed at the two people who had abandoned us to a very unforgiving world.

Duane’s broken bones healed, but he was changed. When he finally settled down and decided to get married I was happy and relieved. He’d bought several beautiful acres of land in Basin, Wyoming. He and his wife were expecting a baby. When his son was born, my brother transformed. He taught his boy everything that he had had to teach himself: how to fish, hunt, and how to create things. Duane spent time with his son and gave him every bit of the love and affection that he himself had been denied. My brother was finally finding peace and stability in his life.

I too had married and had a son of my own. My husband was going to graduate school in Austin, Texas. We had only been in Austin for eight months. On a pleasant March evening, before the humidity had set in, my husband, son, and I had gone out for a walk in the neighborhood. When we got back my dad had left an urgent message on our answering machine. When I called back, I was immediately gripped by the painful, lost, and lonely episodes my brother and I had shared. Only now I realized, I would never have the chance to see him again, or to say I was sorry for not being there when he needed me.

I was told Duane had left Basin to drive to Greenriver. He had a small trailer there; he worked Monday through Friday and came home on the weekends. He had graduated high school, but that was all he had for formal education. Everything he knew he had taught himself, so he was forced into taking blue-collar jobs far away from home to make ends meet. On the road to Greenriver my brother followed a short distance behind a pickup. They were traveling at a safe speed. Coming toward them was a big welding truck, speeding. The woman who was ahead in the pickup later said in court she saw the welding truck weaving and then it crossed the yellow line into my brother’s lane. Welding trucks weigh anywhere from 10 to 12 thousand pounds. As this one swerved it hit the driver’s side of Duane’s Ford F-150 with such impact that the cab was blown apart and my brother thrown out. Duane never wore a seat belt because my dad said they did more damage than good. The guy in the welding truck was so drunk he never knew what happened. He barely got a scratch.

My brother had had premonitions. This fact weighs heavily on my heart and mind. He was six and a half years older than me, and growing up we weren’t close. As adults we had even less in common, but what I understand now is that throughout my brother’s life he overcame the miseries of his childhood. The learning disabilities, the judgment from others, and isolation only made him a better man, which was evident in the way he treated and loved his family.

In his last days, dark clouds hung over him and he sensed something was not quite right. He knew he needed to get that clean running Buick for his wife, he knew the beloved dog had to stay safely at home, and he knew he needed to speak to our mother. He placed that last call, wanting to talk, but only leaving a message.